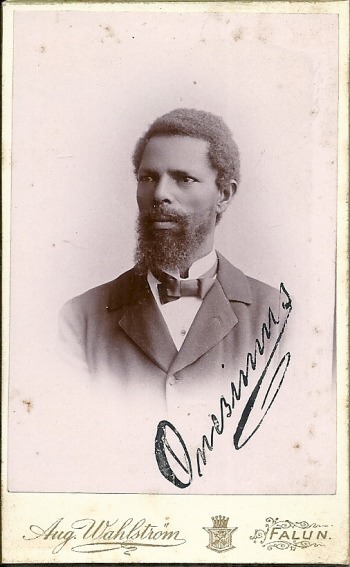

MEKURIA BULCHA

University of Uppsala, Sweden

A BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

Onesimos, whose birth name was Hiikaa, was born sometime in the middle of the 1850s in the region of Ilu Abba Bor in the western part of Oromo land. In his writings Onesimos refers to himself consistently as nama biyya Oromoo or “a man from the country of the Oromo”. When he was about four years old he was kidnapped and separated from his widowed mother by slave-traffickers. He was freed from slavery by Werner Munzinger, a Swiss scholar and adventurer who worked as a consular agent of the French, British and Egyptians at the Red Sea port of Massawa.

Before that Onesimos was sold four times and given the name Nasib by one of the persons who bought and sold him. Since Munzinger bought slaves to set themfree, he handed Onesimos over to the Swedish missionary station in Massawa in 1870. Then Onesimos was about 16 years old. In Massawa he started as a servant with one of the missionaries. He was the first Oromo to be converted to the protestant Christian religion. Onesimos was his baptismal name.

The aim of the Swedish Evangelical Mission when it arrived in 1865 in Northeast Africa was to convert the Oromo people to Christianity. However, as the way to the Oromo country was closed in the north by Abyssinian kings and warlords, the Swedish missionaries stayed at Massawa waiting for the opportunity to penetrate the interior and reach the Oromo country. Meanwhile the missionaries were gathering, educating and converting Oromos who came to Massawa as victims of the slaved-trade that plagued Northeast Africa at that time. Onesimos was the first pupil at the school opened by the Swedish Evangelical Mission for that purpose (Dahlberg 1932: 16).

From the very beginning Onesimos showed an insatiable thirst for knowledge. At the school Onesimos studied religion, history, geography, arithmetic and languages. Soon after he completed his education at the Massawa school the missionaries who were impressed by his capacity and interest to learn sent him to the Johannelund Missionary Training Institute in Stockholm. Onesimos left Massawa for Europe in June 1876 (Dahlberg 1932: 18). He studied at the Johannelund Institute for the next five years and graduated with a teacher’s diploma in 1881. He was also commissioned as a missionary (Dahberg 1932).

Immediately after his graduation he left Sweden and came back to Massawa in October 1881. Back in Africa he started to teach at his former school which was moved to Munkullo outside of Massawa town while he was in Sweden. At that time preparation for an expedition to Oromoland was underway at the mission station. Onesimos joined the expedition to realize his greatest wish and dream of returning to his native land to teach his people what he had learnt.

Since a previous attempt to reach Oromoland through Abyssinia had proved unsuccessful, the 1881 attempt or the so-called second Oromo expedition was made through the Sudan to Wallaga. The expedition set off from Massawa in November that year and reached the borders of the Oromo country after a journey that took two months on the Red Sea, through the Nubian Desert and on the River Nile. On their arrival at the frontier of Oromoland, Onesimos and his colleagues were misinformed about the security situation on the road to the Oromo country and were persuaded to go back by a European called Marno Bey who was an agent of the Egyptian Khedive at the Sudanese border post of Famaka (Dahberg 1932: 29; Aren 1977: 252-254).

The return journey was arduous and disastrous. Two members of the expedition, G.E. Arrhenius, a Swedish missionary and leader of the expedition, and a young Oromo named Filipos, died and were buried on the way (Dahlberg 1932: 30-31). Mighty sandstorms, lack of water and several attacks of fever had to be endured in the Nubian Desert. Onesimos and the rest of the expedition returned to Munkullo in the middle of 1882 after about eight months of a gruelling journey (Dahlberg 1932: 31).

Back in Munkullo Onesimos resumed his teaching duties. In addition he also “set about the most important part of his life-work: that of creating an Oromo literature” (emphasis added , Aren 1977: 262). Onesimos started his literary work as a translator of short religious books. The first two religious works he translated were John Bunyan’s Man’s Heart and a book of religious songs. In 1883, Onesimos had to stop his translation work to once again join another expedition, the third Oromo expedition, to his native land. The missionaries had through correspondence managed to get permission from Menelik, the then king of Shoa, to pass through his country to the Oromo kingdom of Jimma. According to the information that the missionaries had received through traders coming from his land, Abba Jifaar II (1861-1932), the young Mooti (king) of Jimma, was eager to introduce modern education to his people and was interested in receiving missionaries as teachers (Aren 1977: 259).

The third Oromo expedition consisting of Onesimos, his wife Mihret, a young Oromo named Petros and the two Swedish evangelists Pahlman and Bergman left Massawa during the latter part of 1884 and arrived in Shoa via Tajoura (Djibouti) and Harar early in April the same year. On their arrival at Entoto, the new seat of Menelik in an Oromo territory conquered about a decade earlier, the Shoan King denied that he promised them passage through his land and ordered them to immediately return to the coast. Onesimos commented about this incident in a letter dated 23 June, 1886:

It is saddening that even this time we had to be chased away as if we were instigators of rebellion. … We hoped and enjoyed to come to our land which we missed for such a long time (Dahlberg 1932: 34).

Menelik’s behavior towards Onesimos and his colleagues was related by some observers with the awaj (decrees) of his suzerain, Emperor Yohannes IV who ruled Abyssinia from Tigray, regarding religion and missionary activities in his empire. However, the reason behind Menelik’s refusal to allow the expedition to the interior of Oromo land seems to be more than that.

To begin with, it is doubtful whether Menelik who was in the middle of his conquest of Oromo land was happy to have in that territory educated and conscious Oromos like Onesimos who aspired to teach the Oromo people in their own language. It was also unlikely that Europeans who showed interest mainly in the Oromo, as the Swedish missionaries did at that time, were tolerated by his court. In order to prevent European weapons from reaching them, Menelik, in fact, was trying to isolate from the outside world the numerically superior Oromo he was conquering or was planning to conquer. And he was successful in doing so.

ONESIMOS NASIB’S OROMO LITERATURE

Having failed to reach its destination, the third Oromo expedition returned to Massawa in April 1886. Onesimos started once again to teach and translate. Meanwhile the number of Oromo slaves reaching Massawa and other coastal towns was increasing partly because of Menelik’s conquest of Oromoland and, as the life-histories of some of the slaves freed and brought to the mission station show, his direct involvement in the slave trade. However, the Italians who were in the process of colonising the Red Sea littoral of what was later to be named Eritrea combated, with some vigour, the freight of slaves across the sea to Arabia. This meant that more and more Oromo youth of both sexes (most slaves reaching the Red Sea coast were between the ages of 13 and 15) were liberated and sent to the Swedish Mission for support and education.

In addition to translating the Scriptures, which he now considered as the mission of his life, Onesimos found much joy in teaching these boys and girls. Together with him, these victims of the slave trade were, as will be discussed latter on, destined to play important roles in the laying the foundations of Oromo literature and the introduction of modern education and missionary work in the western parts of Oromo land

Onesimos Nasib’s literary works were both religious and secular. He wrote and/or translated most of them between 1885 and 1898. During those thirteen intensively active years he translated seven books, two of them with Aster Ganno, one of the young girls liberated and brought to the missionaries in 1886. Some of the books were short volumes. He wrote an Oromo-Swedish Dictionary of some 6000 words (Nordfelt 1947: 1). As the leader of an Oromo language team, to be discussed in a latter section of this paper, he also contributed to other linguistic works.

The first work (translation) by Onesimos was . This was a small book of religious songs published in 1886 at the mission’s printing press in Munkullo. The book was revised and published in 1894. Several editions of Galata Waaqayoo Gofta Maccaa have appeared since then and it is still in use today. The next work translated by Onesimos was The New Testament or Kaku Haaraa which was completed and published in 1893. Together with Aster Ganno he completed and published Jalqaba Barsiisaa or the Oromo Reader in 1894. The 174 pages long reader contains a collection of 3600 words and 79 short stories most of which were collected from Oromo oral literature.

Onesimos Nasib’s most significant contribution was the complete translation of The Holy Bible or Macafa Qulqulluu which was printed in 1899 at St. Chrischona in Switzerland. Onesimos travelled to Europe and stayed about nine months in Switzerland to assist with proof-reading and personally supervise the printing. He made also his second and last visit to Sweden while printing was in progress. Onesimos’ translation of the Bible has been described by historians and linguists as a great intellectual feat. Dr. Gustav Aren wrote that “the Oromo version of the Holy Scripture is a remarkable achievement, it was to all intents the fruit of the dedicated labour of one man, Onesimos Nesib” (Aren 1977: 385). Onesimos was quite happy about the result of his labour. Although he

foresaw that scholars in Europe would criticize him for having not used the Greek and Hebrew texts, … he was not worried about their censure. He was confident that his translation represented pure and idiomatic Oromo. He remarked that it would take trained philologists many years to produce a better version (Aren 1977: 385).

Indeed, ninety years have passed since Onesimos translated the Scriptures and no new translation of the complete Oromo Bible has yet been made primarily due to the ban imposed upon the Oromo language during this period by the Ethiopian Government.

In the same year as the complete Oromo Bible came out, two other works translated by Onesimos, Katekismos which is the Oromo version of Luther’s Catechism and John Bunyan’s Mans Heart bearing the Oromo title Garaan Namaa Mana Waaqayo yookiis Iddo Bultii Seetana, were published. The translation of Birth’s Bible Stories entitled Si’a Lama Oduu Shantami-Lama by Aster Ganno and Onesimos was printed at the same time.

THE OROMO LANGUAGE TEAM: A MINIATURE OROMO ACADEMY IN EXILE

Onesimos was assisted by a team of Oromos liberated from slavery and sheltered at the Swedish Mission station of Geleb in the highland of Mensa in Eritrea. Dr. Fride Hylander wrote about the team that,

As the interior of the country seemed to be closed, the pioneers in Eritrea made themselves ready for a future advance by gathering a group of intelligent and promising Gallas13 and giving some a refuge at Geleb, in the province of Mensa. Here they were engaged in education and translation and formed a “Galla-speaking colony”, the leader of which was Onesimus (Hylander 1969: 83).

The Oromo language team which was organized about 1890 consisted 15 to 20 members. However, besides Onesimos and Aster, Lidia Dimbo, Stefanos Bonaya who was originally from Lamu in present day Kenya, Natnael, and Roro were among the active members of the team. Nils Hylander, a Swede and close friend of Onesimos from his school days in Stockholm, joined them in 1891. The available sources indicate that Hylander had a very genuine affection for the Oromo and their language about which he wrote to his colleagues in Sweden in this enthusiastic manner:

The beauty of the Galla language cannot be exaggerated. Italian and Galla are…the most beautiful languages in the world. It is a pleasure to read and study them.

He learnt it very quickly and contributed to the work of the team enormously. However, Hylander and Stefanos Bonaya left the team in 1893 to go to Lamu, Zeila and Harar to once again try to reach the Oromo country from that direction. The attempt was in vain. Natnael died of tuberculosis the same year. The rest continued the work with zeal and dedication.

The members of the team contributed in different ways in the preparation of the background literature for the educational and missionary work to be launched in Oromoland. A vocabulary of about 15000 words were collected with the aim of compiling a dictionary, facilitating the translation of the Scriptures, and preparation of educational literature. Aster Ganno, linguistically the most gifted member of the team, wrote down from memory a collection of five hundred Oromo songs, fables and stories. Some of the stories were included in the Oromo Reader mentioned above. A comprehensive grammar of the Oromo language was also prepared. These works were left unpublished.

The work that Onesimos and his language team had accomplished at Geleb can, without doubt, be seen as the first and so far the only significant step towards creating an Oromo literature. These men and women, freed from the cruel grips of Abyssinian and Arab slave-traders by the humanitarian acts of individuals and ironically Italian colonialists and supported by the Swedish missionaries, toiled in a foreign land to make afaan Oromoo a written language with the hope of returning one day to their native land and spread literacy among their people. These hopes were only partially fulfilled.

When the members of the Oromo language team finally returned home, they found conditions in their country radically and negatively changed. Oromoland was conquered and colonised by the Amhara between 1875 and 1900 and the Oromo had lost their freedom. The conquerors were in the process of imposing their own language, Amharic, and their version of Christianity on the Oromo. Therefore, the efforts that these pioneers made to develop Oromo literature and teach the Oromo to read and write in their own language were frustrated by the Imperial Ethiopian government and its partner the Coptic Church.

The ban that the Ethiopian rulers placed on afaan Oromoo during the past 90 years made further development of the work started by them virtually impossible. Nevertheless, the efforts of Onesimos and his colleagues in the area of Oromo literacy were not fruitless. As will be discussed further on, they had, and continue to have, influence on Oromo consciousness and education.